“The mural was born out of a wish to find ways to reaffirm our connectedness as a community even while the needs of addressing covid have isolated us,” shared KVH founder, Bennett Dorrance.

This latest endeavor is just one of many in Kohala’s history of unified strength in the face of adversity.

With the idea of art and story as a heart connection, resident artist for KVH, Raven Diaz and outreach director Joel Tan decided on a mural project that would enclose the slab where the KVH main building once stood, becoming a meeting place surrounded by Kohala stories rendered in art.

Community mural artist Kanoa Castro and his two daughters, Kekapa and Kawelo working on the pueo panel. Photo courtesy of Raven Diaz

Community mural artist Kanoa Castro and his two daughters, Kekapa and Kawelo working on the pueo panel. Photo courtesy of Raven Diaz Starting in May 2020, Joel and Raven began to lay the ground work. They invited Kanu o ka `Āina principal and community artist, Kanoa Castro to join the team and spent two months interviewing kūpuna and other community members to gather stories and ideas to be featured in the mural. “We wanted to highlight who and what Kohala is during times of challenge, how we respond and what's important,” explained Raven.

Notices inviting ideas were also posted all around the community that led to three Zoom sessions and many phone conversations. “We kept it real broad like: What is important for us to know about Kohala? If people were born and raised here we asked about history and traditions; if they had moved here, we asked about their experiences.” explained Joel.

These conversations, “Sparked ideas behind the mural and we turned those ideas, stories, thoughts into visual images,” explained Kanoa.

Meanwhile the KVH maintenance crew built the walls around the slab and painted them with yellow primer, creating a canvas ready for Raven and Kanoa to pencil in the stories and by mid-June the panels were ready to come to life.

The next step was to lay down a base coat or background. A call out to the community yielded a diverse group of painters for seven painting days throughout the rest of June until the end of July. “It was a mixed crowd. Elders, local artists and a lot of keiki,” said Raven.

At the entrance to the plaza are two sheets, one with the QR code for the self-guided tour, available any time. The other is a long list of names of the many contributors to the project.

"It's such a powerful process when you paint and think about something then it shows up in your life." Photo courtesy of Raven Diaz

"It's such a powerful process when you paint and think about something then it shows up in your life." Photo courtesy of Raven Diaz The mural, which encloses the square, is a mixture of the Kohala community’s cultural, historical and ecological mana`o.

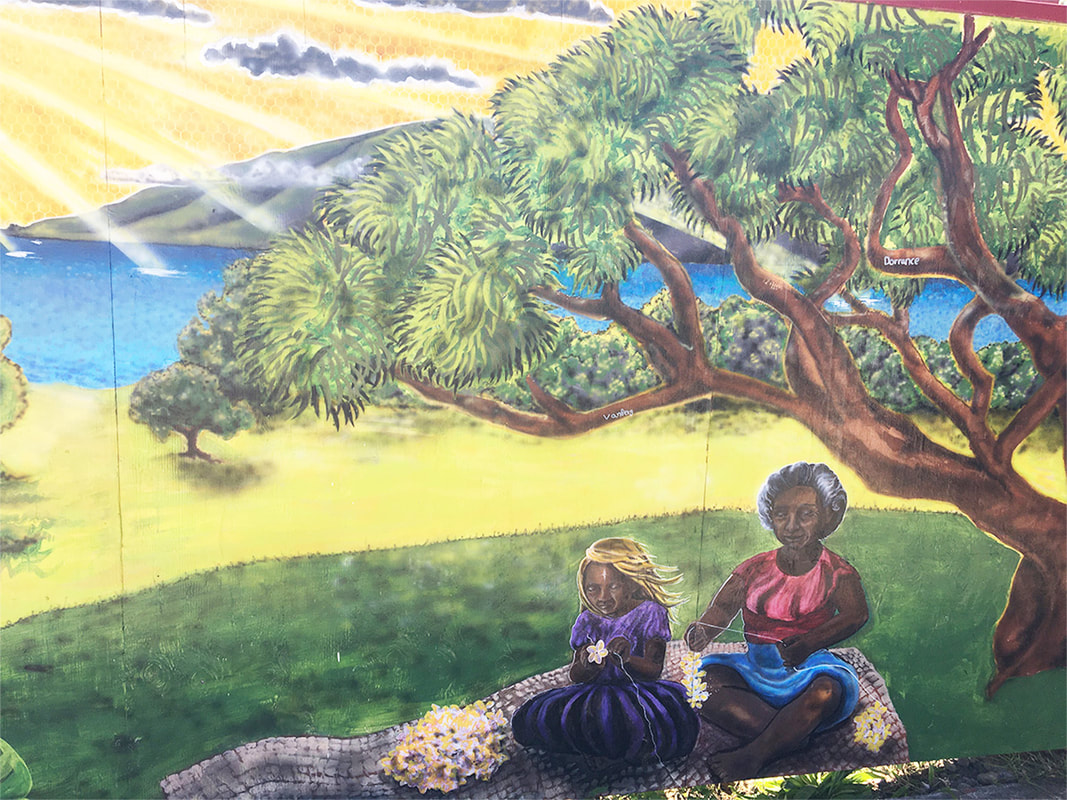

The first panel is a pastoral scene that highlights the essence of Kohala. Rolling green pastures and pu`u; and grazing horses, highlighting Kohala ranching; all flooded by sunrays kissing the land and backed by ocean waters. A kupuna is sharing traditional knowledge with a keiki while sitting under the koaia tree, also known as the “Communitree”, where people can add their names to the leaves.

Two stories relating to sustainability and facing challenges are pictured in the mural. The stories of I`ole the rat are quintessentially Kohala lore and many of the participants in the talk story sessions mentioned them. The panel shows a graphic of the story of how I`ole the rat saved the people from starvation and features the net filled with all the harvest hung in the heavens by Chief Makali`i. I`ole is scrambling up a rainbow to gnaw through the ropes securing the net, releasing the food to all the people.

The food shortages caused by the pandemic are just the latest in the challenges faced by Kohala folks and the spirit of generosity and sharing what you have captures the spirit of the community. The next panel on the wall is of our canoe Makali`i. A traditional responsibility of the canoe and her navigators is to provide food for the people, but Makali`i also represents a community pulling together with generosity.

Another traditional Kohala story shared was Punia, which is illustrated on the makai side wall. The story is told in a series of images that creates a bridge between past and future. In the story, Punia’s father is eaten by a shark when he is diving for lobsters. With his father gone, Punia takes on the role of food provider and finds a way to outsmart the sharks, and emerges victorious.

The story wall of Punia bridges from historic legend to contemporary times and inspires the images that follow. Punia and his mother receive a flag in commemoration of a fallen soldier who, just as Punia’s father, was taken before his time.

In the final panel, by receiving the lei kukui, a symbol of lasting strength, Punia follows his legacy and goes on to become a medical doctor who, with a caduceus in one hand and soil in the other, champions social justice and respect for the `āina.

Featured on the wall parallel to Punia is a representation of the deep spiritual roots that underlay the community. At the center of the display are three pahu drums, eliciting the rhythmic sounds of ancient hula, at the heart of Hawai`i’s cultural practices.

This is bordered by a panel depicting three of the many sacred sites or heiau, with Kohala Mountain, an important water source, in the background. The Mo`okini heiau, which is near King Kamehameha’s birthplace, was rebuilt in the 13th century through the efforts of 18,000 stone passing men, stretching from Pololū. Mo`okini was Kamehameha’s spiritual home until he was advised to build a heiau in preparation for his enormous task of unifying the islands. Again, a massive effort ensued with thousands positioned in a work line and resulted in Pu`ukoholā heiau. The third site pictured, Ko`o Heiau Holomoana, a navigational heiau located just south of Mahukona, is an historic training ground for young navigators and a place of ceremony.

Kohala’s history is immersed in the legacies of King Kamehameha, who exemplified strength and resourcefulness. The panel bordering the pa`u on the other side is a representation of the `aha`ula or royal cape worn by Kamehameha, made up of the yellow `o`o feathers contrasted with the red feathers of the apapane.

The east wall speaks to the ecology of Kohala and features the many plants that have fed Kohala for generations. Many of the Kūpuna spoke of gathering food from the ocean and the cliffs of Kohala. The first panel pictures opihi and at the bottom of the cliffs, tucked away in caves are menpachi, a favorite of Kohala fisherman, pictured at the far end of the east wall.

Another panel features Kalo an essential food plant brought to Hawai`i by the first Polynesians. There are many different kinds of kalo and Kohala has its own special variety called bakatade, which is Japanese for hard-headed.

Also featured is breadfruit, an abundant food provider; and an awa grove, created by Eric Dodson, Kohala artist and medicinal plant grower. Awa is a canoe plant that has many uses and has been an important part of Kohala’s la`au lapa`au, as well as being a ceremonial drink prior to big endeavors such as ocean voyages.

Language of Lei

Lei are woven throughout the mural, just as they are woven throughout Hawai`i life. 'Ohi'a lehua, ancient symbol of the strength of Pele graces the heiau panel. In the panel representing Kamehameha, it changes to a unique Kohala plumeria lei, inspired by Aunty Maile Napoleon, formed with pedals bent back to create a rounded shape.

The lei plumeria transforms into a lei hala in the next panel, representing the completion of a phase and the starting of a new one, and for talk story participants a reminder of a special grove of hala in Niuli`i, the location of an historic sugar cane camp.

Feathered Spirits

The mural also includes a large image of pueo, a quiet guardian and aumakua for many families. Participants in the talk story sessions mentioned encounters with pueo that signified a warning or the marking of an important event.

Centered on the east wall is a large image of the `iwa or frigate bird. The `iwa, whose name means thief in Hawaiian, is known for its extraordinary ability to steal fish from the beaks of other birds in mid-flight. The name Ka`iwakīloumoku was given to Kamehameha to commemorate the “stitching together” of the Hawaiian islands, and connotes someone with great expertise and daring.

The essence of Kohala is hard work, pulling together, resourcefulness and a spiritual connection to the natural world, and the mural project has provided an opportunity to build anew from the ashes. “It's such a powerful process when you paint and think about something then it shows up in your life,” concluded Raven.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed