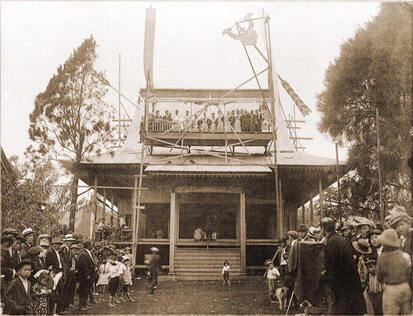

1918 dedication of the new temple. Photo courtesy of NHERC Heritage Center.

1918 dedication of the new temple. Photo courtesy of NHERC Heritage Center. In 1868, the first Japanese immigrants arrived in Hawai‘i to face harsh conditions in an unfamiliar land. They were forced to labor for long hours in sugarcane fields, with no traditional social structures such as the religious practices they left behind. This led to an untenable situation.

The next group of Japanese workers, who arrived in 1885, were under government contracts between Hawai‘i and Japan, and were promised better conditions. Instead, the harsh treatment by the field bosses continued.

Sometime in 1894, the Imperial Consulate General of Japan, Hisashi Shimamura, paid a visit to the Hāmākua Coast. During that visit, members of the Japanese immigrant community suggested the idea of building a home temple in Hāmākua. Mr. Shimamura was so pleased with the idea that he pledged $300 to get construction underway.

Temple founding members Tanikichi Fujitani and Shoichi Hino were instrumental in securing the pledge from the Japanese Consulate. The rest of the $3000 construction costs were raised by Mr. Fujitani and the founding Reverend Gakuo Okabe, who visited house-to-house, collecting donations.

“When times were tough, they only ate bananas to survive in their tireless effort to obtain donations,” said youngest active temple member Sandy Takahashi. “Reverend Okabe was known to travel around carrying an Amida Buddha statue on his back. He would tirelessly walk around with it, spreading the teachings of Buddhism and raising funds to build a home temple,” she added.

Opened in 1896, the original temple, which was named the Hāmākua Bukkyo Kaido (Hāmākua Buddhist Temple), renamed the HJM in 1951, was located in Pa‘auhau Mauka, the geographic center of the five sugar plantations.

The oldest Japanese sanctioned Buddhist temple in Hawai‘i and possibly the United States, the 24 by 36-foot structure stood on an acre of land, surrounded by sugarcane fields, with another acre designated for the cemetery. When the current temple was built, this original building was converted into a kitchen and dining hall, which is still in use today.

Current temple altar. Photo by Sarah Anderson

Current temple altar. Photo by Sarah Anderson In 1909, Reverend Ryoyu Yoshida became the fourth minister to serve at the HJM. It was under his leadership that a new temple, Konpondō (main prayer hall), was completed in 1918, under the direction of Umekichi Tanaka. Mr. Tanaka had moved back to Pa‘auhau in 1916, and had been trained by his father as a miyadaiku.

Miyadaiku carpenters only build shrines and temples, use no nails or metal of any kind and are renowned for their elaborate wooden joints. The buildings they construct are among the world’s longest surviving wooden structures, which is certainly borne out by the 102-year-old HJM temple.

The Pa‘auhau plantation donated the materials, built a road to the site, and helped haul materials there; however, the construction was a community project with more than 270 people directly involved. With the efforts of several carpenters under the supervision of Mr. Tanaka, and only working weekends, the construction took two years.

The plantation also gave permission for the removal of four koa trees from the forest, located at the back of the property. These were used to carve the two distinctive transoms guarding the altar and the altar piece itself.

When the temple was finished, a lean-to was created for the koa logs. Eizuchi Higaki, whose youngest son George is a current temple member, was a plantation machinist. Mr. Higaki, along with Mr. Tanaka and another unknown carpenter, came to the temple every day after work for two years until the carving was finished. Each hand-carved transom depicts a fierce dragon a-swirl amidst an elaborate wave design, symbolizing a close connection to the oceanic world.

Gravestone of Katsu Goto. First grave in temple graveyard. Photo by Sarah Anderson

Gravestone of Katsu Goto. First grave in temple graveyard. Photo by Sarah Anderson The HJM served as a place of worship where immigrants could gather as a community and take refuge from the rigors of plantation work. Along with regular services, the temple offered Sunday school, kabuki-type plays, music, and traditional crafts such as shishu (Japanese embroidery) taught by Mrs. Yoshida (Reverend Yoshida’s wife).

The temple’s cemetery along with the stories of the many generations of temple members, tells the history of an island community that spans across the Pacific. One of the first graves, once the temple was built, was that of Katsu Goto, who arrived in 1885. Mr. Goto became a spokesman in a labor dispute between Japanese workers and the plantation, and in October 1889 was found lynched from a pole on main street Honoka‘a. When the temple was finished, members transferred his remains to the temple cemetery and erected a large gravestone. Revered in his hometown of Oiso, Japan, the municipal museum there has created a memorial exhibit honoring Mr. Goto.

The cemetery has an array of headstones ranging from carved marble, to carefully arranged boulders, to simple stones. The stones are the resting place of unknown immigrants whose families had perhaps returned to Japan. It is also the resting place for Japanese laborers whose graves were transferred from nearby Kukaiau.

Longest serving reverend Kogan Ekuan. Photo courtesy of NHERC Heritage Center.

Longest serving reverend Kogan Ekuan. Photo courtesy of NHERC Heritage Center. Reverend Kogan Ekuan served the community from 1937–1977 and is remembered fondly. However, his years of service were interrupted by a twist of fate that highlights the ongoing connection between Hāmākua and Japan, despite world events.

Reverend Ekuan was in Japan tending to his ailing mother when the US entered World War II. Earlier in 1941, his wife Kimie had died while giving birth to twin daughters, along with one of the twins. Reverend Ekuan’s mother-in-law, Tome Oda, came from O‘ahu to take care of her newborn granddaugther and the Ekuanʻs other two young sons. During the time Reverend Ekuan was away, Tome kept the mission open as a community center and gathering place. Upon his return in 1948, services and temple activities resumed.

Daughter Yoshiko remembered, “When my father came back, he started a Sunday school; we went down makai for services. At the temple we had the Hana-matsuri service to celebrate the birth of Buddha. And what was really cute was my father made a play, a shibai, where the Sunday school children would be the actors and actresses.”

Temple president Masa Nishimori, and members Suye Kawahima, Sandy Takahashi and George Higaki, whose father carved the transome. Photo by Jan Wizinowich

Temple president Masa Nishimori, and members Suye Kawahima, Sandy Takahashi and George Higaki, whose father carved the transome. Photo by Jan Wizinowich The handful of elderly members continue to keep the temple in perfect working order, preserving their history and honoring their ancestors. Along with a contingent of elderly members who do an annual work day to prepare for Obon, church president Masa Nishimori is a constant presence.

“Trimming trees, hauling filled wheelbarrows clear across the property and back, mowing the yard, raking leaves, and doing various handyman work are just some of the things he does, so that the property is kept in good condition,” commented Sandy.

The future of HJM is uncertain, but it continues to be a regular destination for both Japanese and mainland visitors. The remaining members hope to see it preserved for future generations as a center for learning and remembrance.

Every Buddhist temple contains a munafuda (dedication board), which is placed somewhere high in the rafters. Like a time capsule, along with a recording of the construction details including names of the people and funders, the Hāmākua Jodo Missionʻs munafuda also contains a prayer for the future:

brightly.

May the wind and rain be timely and disasters and calamities not arise.

May nations be bountiful, people be safe, and armies and weapons not used.

Let us revere virtue and humanity and cultivate respect and humility.

Historypin.org: Hamakua Jodo Mission

Visit: North Hawai‘i Education and Research Center’s Heritage Center

RSS Feed

RSS Feed