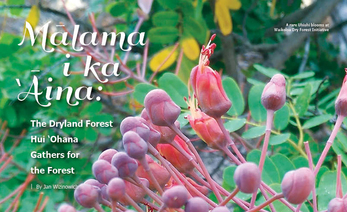

Uhiuhi

Uhiuhi Six of those forest gems are the beneficiaries of active restoration efforts by the members of the Dryland Forest Hui ʽOhana (DFHʽO), which forms a modern ahupuaʽa, not demarked by the traditional ahu, but by the manaʽo (belief) of the people who are quietly working to preserve and restore those remnants.

The hui began when Puʽuwaʽawaʽa volunteer coordinator, Elliot Parsons, asked fellow dry forest conservationists Jen Lawson and Wilds Brawner and Kealakaʽi Knoche to help him verify the last known wild growth of mao`hau hele (Hibiscus, spp. Brackenridgei, the Hawaii State flower).

“We all realized that collectively we had a lot more knowledge about dry forest ecosystems together than we did individually and we wanted to keep meeting at each other's sites, learning from each other and learning each other's plants, out-planting and restoration techniques,” says Elliot.

The hui soon grew from three projects: Waikoloa Dry Forest Initiative, Ka'ūpūlehu Dryland Forest Preserve and Pu`uwa`awa`a Volunteer Work Program, to include The Nature Conservancy’s Kīholo Bay (fish pond) Restoration Project, the Mauna Kea Forest Restoration Project and the newest member, Kaloko-Honokōhau National Park.

Discovery Trail Mauna Kea Forest Restoration Project

Discovery Trail Mauna Kea Forest Restoration Project The Mauna Kea Forest Restoration Project (MKFRP), “The only subalpine dry forest in the state,” according to coordinator C. Kalā Asing, is at the top of the DFHʽO ahupuaʽa. It’s early on a Friday morning and the hui is gathered on Saddle Road at the Kilohana access gate. Equipped with various tools, we receive our instructions and travel up a rugged road to the palila habitat enclosure. By the end of the day the initial Discovery Trail, a one mile interpretive loop, has been cut.

Waimea born and raised, Kalā returned to Hawaiʽi Island from school and work on Oʽahu. “I was very excited that they had created this hui. First and foremost, just the practicality of being able to join forces with so many professionals. The amount of work we get done on hui days is absolutely ridiculous,” says Kalā.

Wiliwili Waikoloa Dry Forest Initiative

Wiliwili Waikoloa Dry Forest Initiative “Whether it’s clearing weeds, planting trees or building trails, the hui is awesome. On one hui day crews cleared four acres of fountain grass, a task that would have taken the Waikoloa crew a month,” says Executive Director Jen Lawson.

“Have you tried this?” is a question that comes up often when the hui gathers and discussions range from land reconstruction to wildfire, which is a constant threat. “The collective mana'o of the hui helps to brainstorm and vet ideas about reconstructing the landscape and prioritizing resources in the event of a wildfire through a different set of lenses,” says Jen.

The hui also provides the opportunity to pool information on native species, such as the uhiuhi (Mezoneuron kavaiense), which is a very hard, close grained, black wood used by Hawaiians to make such things as ʽōʽō (digging stick), ihe (spear), laʽau melomelo (fishing lure) and pāhoa (daggers).

“Uhiuhi is an endangered tree and we had 48 of them here (Puʽuwaʽawaʽa) but they were also at Waikoloa. Jen found recruitment (seedlings) over there, but we haven't found too many over here and we’re exploring why that is. It gives us information about the plant. Having a multi-site approach across landscapes is crucial,” says Elliot.

Kipuka Oweowe, Pu'uwa'awa'a

Kipuka Oweowe, Pu'uwa'awa'a A ranching area beginning in the nineteenth century, its current multi-use nature makes for complicated management. “Every project has its complexity. I think we're one of the more complex projects because we have public access trails, grazing and conservation work. There's a lot of different lenses,” says Kealakaʽi Knoche, field coordinator.

The largest of the hui projects, Puʽuwaʽawaʽa is the mauka area of an almost 39,000 acre ahupuaʽa that stretches makai (towards ocean) to Kīholo. Due to its size, the conservation strategy here is to create “exclosures” to protect still viable areas from grazing animals.

At a recent hui day a crew of about 20 tackled fountain grass at Kipuka Oweowe, an almost undisturbed 27 acre area containing mature lama (Diospyros sandwicensis) trees, close to the border with Ka'ūpūlehu.

“As part of this last hui day we were able to clear two to four acres of the fountain grass in the newer 17 acre portion of that area. That's a really big deal for us,” says Elliot.

Kaʽūpūlehu

Kaʽūpūlehu “We're super small, but we're 76 acres of the best lowland dry forest in Hawaiʽi,” says site manager Wilds Brawner.

As soon as you enter Kaʽūpūlehu you are going down a steep slope through native forest. The 70 acre site opens out below the original six acres, where on a recent hui day more than a dozen crew members trudged up the hill with buckets containing about 200 pounds of keiki molina grass, a hardy invasive, as well as several large gnarly mature plants.

“What we're trying to accomplish at Kaʽūpūlehu is to bring the dryland forest habitat back to a state of self-sustainability where the forest can do its best to compete with the weeds out there,” said Brawner. This is evidenced in clusters of hau hele ula (Kokia drynarioides), uhiuhi (Mezoneuron kavaiense), and kauila (Colubrina oppositifolia) that dot the landscape, fruits of previous hui work days.

Kaloko-Honokōhau

Kaloko-Honokōhau Current Cultural Resource Program Manager, Tyler Paikuli-Campbell, looks to ancestral knowledge for guidance. “The fish ponds are the focus as we restore the cultural landscape of the dryland forest,” said Paikuli-Campbell.

“With the hui we were able to remove so much more of the invasive, non-native plants and allow natives to dominate again. It's great to know that there's all these other people and places doing the same thing. It gives us more confidence to push on every day,” adds Tyler.

The Hui uses a raft to ferry out logs at Kiholo

The Hui uses a raft to ferry out logs at Kiholo The large aliʽi (chief) fishpond and its surrounds, located at the north end of Kīholo was gifted to the Nature Conservancy in 2011 by the Paul Mitchell estate. Marine Coordinator, Rebecca Most, who began with the project at its inception, has a master’s degree in Conservation Biology from U.H. Hilo, but for Rebecca, it isn’t just about the science.

“I specifically went to projects that involved the community and put the heart and soul into conservation. I did a research project at Kīholo and fell in love with the place and the community,” says Rebecca.

Rebecca heard about the hui and immediately saw the benefits of pooling resources. “I saw that it would be a great opportunity to learn more about native plants and increase our knowledge about restoration techniques. We're working hard together, but we're talking, bouncing ideas off each other,” says Rebecca. “With skilled professionals, we’ve been able to accomplish much more,” she adds.

The Dryland Forest Hui ʽOhana is sharing knowledge, resources and making connections to work towards the dream that these remnant forest roots will eventually extend out and connect the past with the future. “We’re all pioneers of this place again. We’re the tree planting generation trying to undo some of the damage that we’re now smart enough to understand we’ve done,” says Jen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed