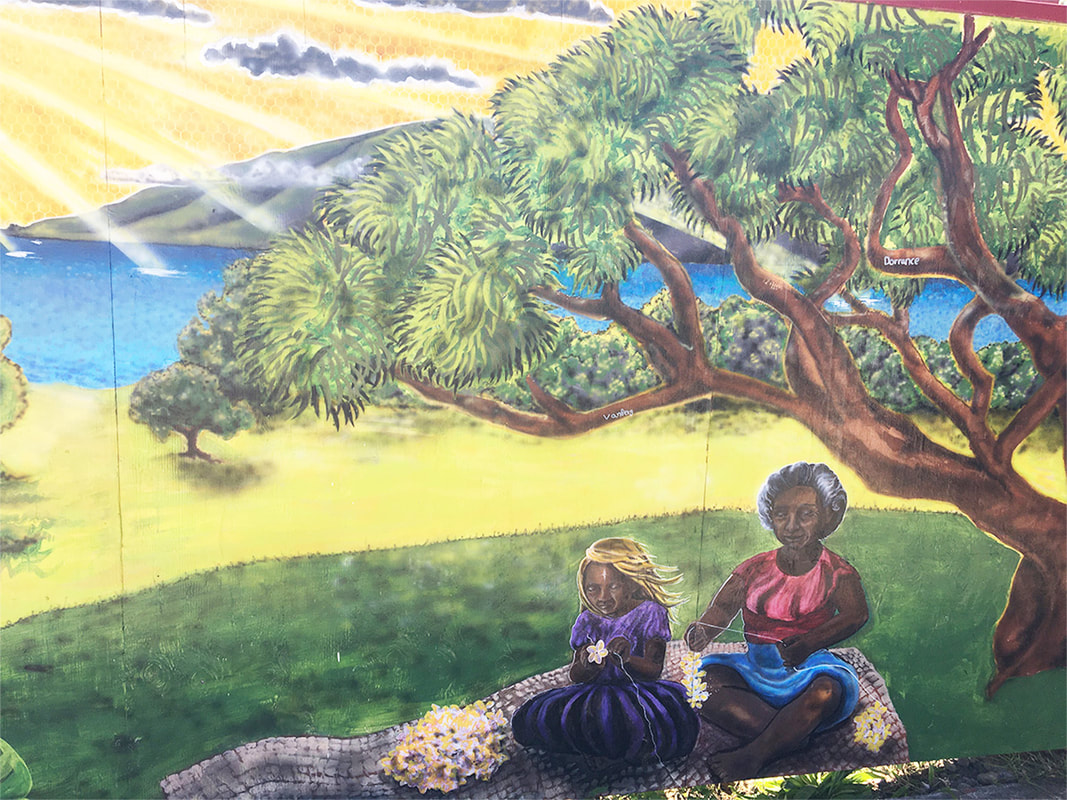

Nani Svendsen is one such person. Along with the hearts and hands of many others, she has created a beautiful refuge, called Kōnea o Kukui. “Kukui means light or enlightenment. I didn’t give it that name; it’s been in my family for seven generations,” said Nani.

Nani in her element. Photo by Jan Wizinowich

Nani in her element. Photo by Jan Wizinowich Nani had an ideal, land-based childhood. “I grew up on the Kohala ditch; we were the last family to live there. My parents’ job was to regulate the water. I was born in Kohala but I was raised in Waiapuka, two miles up where they used to start Fluminʻ Da Ditch. There was nobody around us, the stream ran next to the house, and we were isolated from everyone else. Off the grid. So, it was furo [Japanese bath], kerosene lamps and stove. Lived like that until I was 11,” remembered Nani.

Nani’s ancestors came to Kohala during Kamehameha’s time. “They were from Hana, Maui and they were stewards to the heiau [temple] on the bluff at Keokea,” said Nani. Since that time, the land has gone through many phases and witnessed many family events. At times it’s been a home dwelling, while at other times a refuge.

Perched above Keokea, the botanical residents of Kōnea o Kukui cluster around a stream whose journey feeds into the Pacific at Keokea Beach Park. I arrived at the garden on a sunny day in May, and Nani greeted me at the top. The first view of the garden was from the perspective of a floating cloud just above a lush, orderly jungle of greens and flowers. To the left is a lo‘i (taro patch) and in the center is a small house and a pavilion.

Nani and I talked story for a few moments and during that time, I felt the pull, an irresistible invitation. The trail to the garden slopes downhill and is lined with red and green ti, ferns, coconut palms, begonia, and hala trees. The first thing I noticed is that everything slows, like there is no time at all. A switchback led us further down. We stopped on the trail to be welcomed by a Java rice bird who sat on the branch of a ti plant—it had a lot to say that morning. When it was done talking, we were allowed passage.

A bridge crosses the stream at the bottom of the trail and then we were in the heart of the matter. We passed a pond with lotus blossoms as we climbed up the bank on the other side. Looking downstream I saw into a community of connected beings, a chorus of welcome.

Nani’s many years as a florist are reflected in the garden. The place spoke to her of color, contrast and balance. Where there were disconnected pools, Nani saw a channel of flowing water.

Nani's granddaughter, Kainani, on the trail entering the garden. Photo courtesy of Nani Svendsen.

Nani's granddaughter, Kainani, on the trail entering the garden. Photo courtesy of Nani Svendsen. The Kohala of Nani’s childhood began to be overshadowed by outside pressures that affected both her immediate family and the community. Dismayed and determined to do something about the problem, Nani, Dennis Matsuda, and community members led a successful effort for a drug rehabilitation house for recovering men in Hawi, When the house was set up, Nani turned her focus on her own healing process.

“I decided I wanted to build, what for me, was going to be my happy place. It was about the life or death of me. To find my peace. I knew this place [Kōnea o Kukui] had a stream running through it and I started chopping. I had no idea where I was going to take it, but I wanted to remember my beautiful life. I need to feel this, see it, smell it, be in it,” recalled Nani.

Using a chainsaw, machete, shovels and o‘o bar, Nani began an odyssey of self-discovery. Then she got a call from Wes Markum, director of the rehabilitation house in Hawi, and he asked her about inviting the residents to come work with her. Her first response was, “No.” Hadn’t she done enough? Then her heart spoke, and she realized that, “Most of these people, they’re all islanders removed from their culture and that is one of the important facets to recovery.”

The men came every Wednesday for a few hours. Their hearts came alive with memories. They said things like, “This reminds me of when I was with my grandma and grandpa,” and, “This is like Waipi‘o.” She asked every person about their profession and discovered skills among the men such as a rock wall builder, and landscaper, just waiting to be tapped.

Eventually student groups were coming, and soon Nani was pitching a 20 by 20-foot tent for meetings. She shared, “My husband, Don, decided to build the pavilion. We had to haul everything down this trail. Everybody worked like a team, passing station to station, all the way down the hill. It took about four weeks,” said Nani. Working together with the volunteers changed her husband’s life—it changed hers.

Nani has come full circle and a forgotten treasure has been brought back to life, touching her life and the lives of the many who came to Kōnea o Kukui to work and be healed. “This is a restoration project of a lifetime, hopefully not just my lifetime. It’s layered. So many layers to the existence from this place,” reflected Nani.

When Nani began the garden odyssey, the land was covered in hau, and java plum trees. It was also populated with mosquitoes. When they started to clear it, they discovered a taro farm that hadn’t been used since the mid-1950s. “Once that stopped, the hau became the straight tall timbers that were used by the voyaging canoes,” recalled Nani.

During this initial clearing, Nani’s daughter, Punahele was attending Kanu o ka ‘Āina school. At that time teachers and voyagers, ‘Ōnohi Chadd Paishon and Pomai Bertelmann were looking for materials to repair Makali‘i and to build Alingano Maisu for master navigator, Mau Piailug and they could see that the place had what they were looking for. “They brought the students down and they harvested and packed it up the hill. When they built the canoe, they used hau from here,” said Nani.

As the excavation continued, “We could see the terraces, the original walls and the ‘auwai (ditch). The walls were carbon dated by archaeologist Dr. Michael Graves and he found they were dated between 1570 and 1650. From the head of the ‘auwai down to Keokea,” said Nani.

“Maybe a cultural place, maybe a healing place, maybe a safe place. While I still try to put my finger on it, I get to feel like everything stops. Whatever hassle is going on, whatever trouble I have, whatever trouble somebody else has. If I slowly walk down the trail something shifts, and you walk easy with a little more light in your heart. Maybe I can do this, maybe a week, maybe I can just do this,” reflected Nani.

It was not only the men who were healed. “I had a lot of older women coming to support. They were like the tūtū for the young men, and they worked alongside them. They gave of themselves and they too were healed,” said Nani.

Despite the closing of the Hawi rehabilitation house in 2013, weekly meetings continue at Kōnea o Kukui, with the spirit of the land inviting returning visitors into a healing circle.

Kōnea o Kukui is an unusual project because it doesn’t survive on grants as much as on passion. 90 percent of this is from people’s good-heartedness. “All I am doing is to try to steward this place and keep it with the right intention, to just have a safe space, a feel-good space that honors the ancestors, honors the culture, honors each other,” said Nani. “We are responsible for each other. We are all connected. I believe in energy and I believe that if you are not at your best, there is energy out there to help,” she adds.

The spirit of the land waits patiently and when we call out it answers. “I struggle with the sustainability of the place. Along with everything that has been here there has been trust that it’s going to work,” reflects Nani. “There is an ‘andʻ—itʻs this ‘andʻ it’s nature. I can hear the birds here. I can feel the wind. There’s a connection. We forget. We get caught up so much with daily struggles, that we forget where to go to get our own healing,” reflects Nani.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed