The play was inspired by an event that took place on September 16, 1897, when well over 300 Hawaiians gathered at the Salvation Army Hall in Hilo. Mrs. Abigail Kuaihelani Campbell and Mrs. Emma Aima Nawahi, who traveled throughout the islands collecting more than 38,000 native Hawaiian signatures (97% of the native population, had come to speak about the kue (to stand in opposition) against the annexation of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

A San Francisco Call reporter, Miriam Michaelson, wrote an article about the event, which became the basis for Ka Lei Maile Alii, an audience participation, re-enactment of the meeting. Through the efforts of Pua Case and others, the play has been performed on Hawaii Island beginning in 2012. “I had been in the play as one of the audience speakers on Oahu. I felt that many in our community had not perhaps been given the opportunity to learn about that part of our history. Most of us at the time were not aware of the effort by our people to address annexation. So this was our way of bringing this essential part of our history to our community,” says Case.

The petition, which was ignored, was housed in the Library of Congress National Archives until 1997 when Dr. Noenoe Silva journeyed to Washington D.C. and returned the Kue Petitions to Hawaii. The Hamakua to Kohala portion of the petition will be on display and provides a historical window for the descendants of the signatories and the community, a way to get “a truthful peek into history,” says Case.

The Rickard Family Legacy

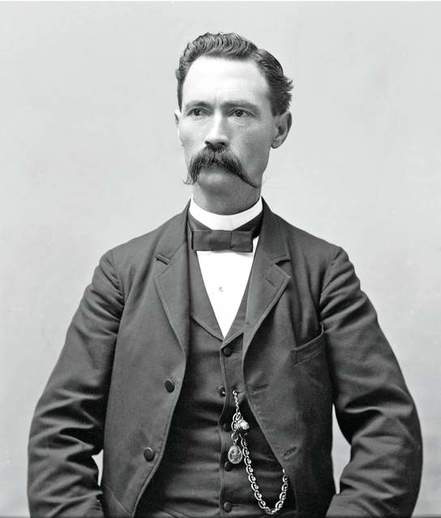

Several of the petition’s signatures bear the name Rickard, a family whose contributions to the Honokaa community will be the subject of an introductory presentation by Dr. Momi Naughton, director of the NHERC Heritage Center in Honokaa. Naughton has created a special exhibit on the Rickard family and will have a traveling version on display.

After coming across several references to the family, Naughton became curious about them and made some phone calls, eventually contacting great grandson, Ryon Rickard. “Right away Ryon was very excited that somebody was interested. From a very young age, he started keeping all these things,” says Naughton.

Through letters and photographs, Naughton was able to create an exhibit rich in the details of a life well lived. Originating in Cornwall, England, Rickard and his wife Nora arrived in the islands in 1866 and after a short stay in Honolulu traveled to Waimea to join his Uncle George, the first family member to come to Hawaii. “He had a blacksmith shop at Hale Kea in Waimea that was a gathering place for expats,” says Naughton.

Uncle George was a great friend of King Kalakaua, “and so when he (W.H. Rickard) got here he was right away in with the alii. In fact Lot Kamehameha was the godfather to his daughter who was born on the ship coming over,” says Naughton.

Rickard was a man of many talents and initially worked as a contractor and engineer for the old Kukuihaele Landing, completed in 1868. He then spent three years as a book keeper for the Kohala Sugar Co. In 1873 Rickard and his entire family moved to Honokaa where they became an integral part of the community. “His mother was a midwife and she literally delivered 100s of babies without the loss of a single mother or child,” says Naughton.

Rickard started a sugar plantation, which with the addition of partners Joe Marsden and Mr Siemsen became the Honokaa Sugar Co. “Rickard was a beloved plantation manager for the Honokaa Sugar Company and spoke fluent Hawaiian,” says Naughton.

Rickard was also known for his hospitality to Hawaiian alii visiting the Honokaa area. “Here’s a letter written by Curtis Iaukea (secretary) thanking the Rickards for hosting Queen Kapiolani here in Honokaa,” says Naughton.

W.H. Rickard showed his loyalty and strong support of the Hawaiian monarchy with his actions. “As soon as the overthrow happened he started working in the community to block annexation,” says Naughton.

He ultimately gave his life for the Hawaiian Kingdom. “In 1895, Rickard took part in the counterrevolution to try to put Queen Liliuokalani back on the throne. He was captured along with Robert Wilcox, Joseph Nawahi and others and imprisoned. During this time he contracted tuberculosis and after his release moved back to Honokaa where he died in 1899,” says Naughton.

Two buildings in Honokaa are memorial to the contributions of Rickard. “The Salvation Army Hall was their last home here. When Rickard died he left his wife Nora with 16 young children to raise and she turned it into a hotel,” says Naughton.

The Honokaa School Auditorium, built in the 1920’s, years after Rickard’s death, is dedicated to the Honorable William H. Rickard, and stands as a testament to his community service. “Each year we begin the play with a presentation that will introduce the play and another part of history. That's why we are bringing Momi and that presentation to Waimea because many of the students that go to Honokaa School have no idea who the armory is named for. I want our students to say, 'I didn't know that was named for a non-Hawaiian patriot of the queen. That’s extraordinary',” says Case.

While the subject of the play, the 1997 Kue is a protest, the play itself is not. “Most of us are not aware of the effort by our people to address annexation and that time period. So this is our way of bringing this essential part of our history to our community. We bring the community together to learn something together,” says Case. “We embrace the entire community and all are welcome,” she adds.

The NHERC Heritage Center, located in Honokaa, is a wonderful way to learn about and experience the richness of Hamakua history. The new exhibit gallery contains a series of collections highlighting various multi-cultural, historical aspects of Hamakua history. It’s open to the public Monday through Friday: 9am to 4pm and Saturdays: 9am to 1pm.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed