Wena is the red glow of sunrise or the rosy glow in a cloud associated with Pele. Photo by Barbara Schaefer

Wena is the red glow of sunrise or the rosy glow in a cloud associated with Pele. Photo by Barbara Schaefer There are many different terms that describe colors. For example, Wena is the red glow of sunrise or the rosy glow in a cloud that can be associated with Pele. Hā‘ena is a red-hot burning, such as rage or anger and is also the name of a place in Kea‘au on Hawai‘i Island that is known as the playground of Hi‘iaka, favored sister of Pele.

“Hawaiian language has more precise names for colors and nuances of color names. I see a yellow ti leaf but the word we use for that yellow is pala, not melemele. It is ripe or aged. It captures the peopleʻs perspective. How they see things around them,” explained Dr. Kimura.

The basic word for cloud is ao, but there are dozens of terms for various clouds. Ao pua‘a describes a grouping of various sized cumulus clouds, resembling a pua‘a (mother pig) with her piglets gathered around her. Malu is Hawaiian for shelter and a ho‘omalumalu describes a sheltering cloud.

Rains are a unique experience depending on one’s location. In Waimea there is a rain called uhi‘wai. Uhi can mean a covering, a veil or film, so uhi‘wai refers to a light misty rain that comes in the afternoon and feeds the crops. In Hilo the misty rain is kani‘lehua, because it quenches the thirst of the lehua blossoms.

Tutu Mary Kawena Pukui, Hawaiian scholar and co-author of the definitive Hawaiian dictionary. Photo courtesy of Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum.

Tutu Mary Kawena Pukui, Hawaiian scholar and co-author of the definitive Hawaiian dictionary. Photo courtesy of Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum. In Hawaiian language tradition, words have power; a name was a person’s most precious possession, a force unto itself. Or in the words of Mary Kawena Pukui, “A name became a living entity...identified a person and could influence health, happiness and even life span.”

Hawaiian names also offer a glimpse into a person’s life. “As Hawaiian speakers, when we hear a name in Hawaiian, its meaning or significance is often apparent. The language carries meaning and the listener is impacted by the meaning and significance of a name,” explained Dr. Kimura.

There are three types of names which refer to the relationship between humans and the spiritual world: Inoa pō, inoa hō‘ailona, and inoa ‘ūlāleo. Inoa pō is a name that comes in the night through a dream to a family member and given to a baby. Pō means night but in a larger sense, it means source, the time before the beginning, a connection with the ancestral world.

An inoa hō‘ailona, or sign name, was found when “a family member might have a vision, or see a mystic sign in the clouds, the flight of birds, or other phenomenon that clearly indicated.” An Inoa ‘ūlāleo, or voice name, might be found when someone hears “a mystical voice speaking a name directly or in an oblique message,” a voice on the wind.

A name from one of these three origins must be given or risk sickness and death. Mary Kawena Pukui’s own birth illustrates this. After she was born, an aunt was given an inoa pō, but she did not bestow the name. Kawena became ill and during a ho‘oponopono the aunt revealed the inoa pō. The original name was ‘oki (cut, severed) and the inoa pō was given, restoring her to health.

Ka'iu Kimura, director of the 'Imiloa Astronomy Center holds one of the charts with name suggestions. Photo courtesy of 'Imiloa Astronomy Center.

Ka'iu Kimura, director of the 'Imiloa Astronomy Center holds one of the charts with name suggestions. Photo courtesy of 'Imiloa Astronomy Center. Naming preserved shared history. Inoa ho‘omana`o are names that provide brief historical reminders of past events. “Let a grandmother call out to a child, ‘Come here, Keli‘ipaahana’ (“the industrious chiefess”) and everyone within hearing remembered Po‘oloku, the beloved chiefess who kept her people busy and prosperous, and even personally dug holes for planting bananas.”

Often a person or place has more than one name such as our own Hawai‘i Island, commonly known as the Big Island but also called Moku o Keawe. Why is that? The answer provides some island history. The name is derived from a 17th century chief, Keawe‘īkekahiali‘iokamoku, great-grandfather of Kamehameha I, whose reign over the island was peaceful and prosperous.

Inoa Kūamuamu: Reviling Names

Some children were thought to need protection from harmful spirits and were given such names as Makapiapa (sticky eyes) or Kūkae (excrement). The hope was that the spirit would be disgusted and stay away from the child. After a few years, the reviled name was ‘oki (cut) and the child was given a new name.

Inoa Kūamuamu were also a kind of negative commemorative name. This kind of naming was used when someone who lived close by had hurt or insulted the family. The family then gave the baby a name that would be a constant reminder of the offense.

Lineage, Prophesy and Tribute

Names were also selected to show family descent, as in the case of ‘Umi-a-Līloa. “Līloa, 50th king in succession after Wākea, the traditional founder of the Hawaiian people named his son ‘Umi-a-Līloa, meaning ‘Umi, descendant of Līloa’.”

Family lines and migrations are also revealed in names, as well as tribute to the accomplishments of the bearer. “Defeated enemies gave Kamehameha I the name Pai‘ea (hard-shelled crab) as a tribute to their conqueror’s impenetrable courage and endurance.”

Students began the workshop with a symbolic ti leaf lei, connecting them to ancestral sources of knowledge. Photo courtesy of 'Imiloa Astronomy Center.

Students began the workshop with a symbolic ti leaf lei, connecting them to ancestral sources of knowledge. Photo courtesy of 'Imiloa Astronomy Center. Over the years, Hawaiian language retained fewer speakers with the influx of outside influences and a new social milieu. Naming traditions, which provide insight into the Hawaiian world view, changed as well.

“Our language captures many aspects of traditional culture that we donʻt practice anymore,” said Dr. Kimura. “If youʻre raised in todayʻs world, itʻs hard to be comfortable about reviling names or commemorative names that may have peculiar meaning. The most common way people think about that kind of name is that itʻs negative or odd. They avoid it,” he added.

A serendipitous series of encounters and events created an opportunity to delve into Hawaiian naming practices and brought the Hawaiian language onto the world stage. Initial plans were already underway to explore the possibility of giving Hawaiian names to astronomical objects discovered from Mauna Kea or Haleakalā. Then, in the fall of 2017 an interstellar asteroid entered our solar system.

Dr. Kimura was asked by his niece, Ka‘iu Kimura, director of ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center, to name this unique new object. Aided by modern day technology, the process he went through mirrored traditional Hawaiian naming practices based in close observation and reflection.

“It appeared to be like something thatʻs coming in to check us out. Some kind of a spacecraft from some outer planet, like a spy. Fairly quickly the name came to my mind: ‘Oumuamua, an advance guard, coming to check us out,” said Dr. Kimura.

A series of informal meetings between Dr. Kimura and Doug Simons, director of the Canada-France-Hawai‘i Telescope, Alan Tokunaga, retired astronomer, and John Defries, a Hawaiian businessman who sparked the idea of using Hawaiian names for new astronomical discoveries, began in January 2018.

This gave birth to A Hua He Inoa (calling forth a name), a program through the ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center. In October 2018 a weekend workshop was held to engage young Hawaiian speakers from the islands of Hawai‘i and Maui in Hawaiian naming traditions.

Students display the final names for the two asteroids. Photo courtesy of 'Imiloa Astronomy Center.

Students display the final names for the two asteroids. Photo courtesy of 'Imiloa Astronomy Center. By the end of the weekend they had agreed on names for the two asteroids: 2016 HO3 was named Kamo`oalewa, Kamo`o meaning a fragment or offspring that will now alewa, orbit on its own; and 2015 BZ509, was named Ka`epaoka`āwela, which is an asteroid near the orbit of Ka`āwela (Jupiter), but is `epa or mischievously moving in the opposite direction.

“This was a new opportunity. These Hawaiian speaking students never thought theyʻd be asked, let alone dreamt that they could use their Hawaiian language and cultural knowledge to name these kinds of objects,” reflected Dr. Kimura.

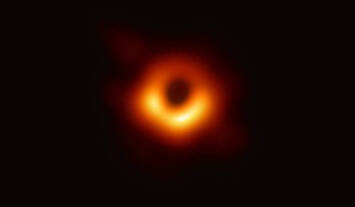

The first image of a black hole, named Pōwehi by Dr. Kimura. Photo source: Hawai'i Tribune Herald.

The first image of a black hole, named Pōwehi by Dr. Kimura. Photo source: Hawai'i Tribune Herald. “We are reviving new generations of Hawaiian speakers, which requires the establishment also of our Hawaiian cultural identity by being involved in renewing this naming process so that someday it can become normal as before. One little way of reconnecting,” concluded Dr. Kimura.

Referenced work:

Nana I Ke Kumu: Look to the Source V. 1 Pgs 94-98

Hawaiian Dictionary. Mary Kawena Pukui / Samuel H. Elbert

papahanaumokuakea.gov/education/cultural_hawaiian_names_wind.html

kumukahi.org

RSS Feed

RSS Feed