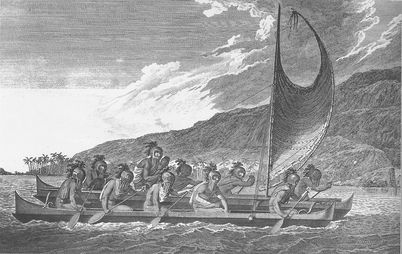

Ancient sailing canoe

Ancient sailing canoe Back on the shore, he helps his men finish rigging the ‘ama and ‘iako and together they step the sail, fastening the stays. Kahakini glances out to sea once more and makes a slight adjustment to the sail.

By now family members join them and they circle the wa‘a and pule for their strength to hold. The canoe is in the water. Kahakini’s heart lifts. Paddles down and the wa‘a comes alive. The steersman points her out while Kahakini searches for signs of the wind that will sweep them in a broad reach to Hāna.

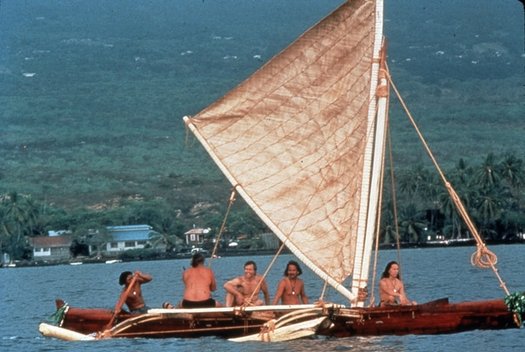

Mauloa, a traditional canoe built by Na Kalai Wa'a

Mauloa, a traditional canoe built by Na Kalai Wa'a When the Hawai‘i Sailing Canoe Association (HSCA) teams depart from Kēōkea Beach Park on May 13, headed for Hāna, they will be reliving an experience that has roots back to the first Polynesians to set out on the ocean.

Scaled down from larger voyaging canoes like Hōkūle‘a or Makali‘i, smaller single and double hulled sailing canoes—like the one in Disney’s Moana, or Palikū, built in a month for ‘Imiloa’s Canoe Festival in 2016—were central to life in Hawai‘i. Sketches and written accounts of Hawaiian canoes under sail from the late 1700s and early 1800s illustrate that paddling while under sail was also standard procedure in old Hawai‘i. The sailing canoe was perfectly designed to tackle almost any condition offered up by the island waters.

“When I think about the traditional Hawaiian sailing canoe and you think of the coastlines and the distances between the islands, you couldn't come up with a better boat. You can sail when it’s light or when it's a little heavy. When there’s no wind you can paddle, and it drafts just a few inches. I can pull up on a beach or I can come in over a shallow reef,” said Kamakakoa canoe captain Kala‘i Miller.

While sailing canoes were used for practical purposes such as fishing, transport and communication, there are also historic accounts of sailing canoe races with equal billing as paddling races. Today’s sailing canoe is a hybrid that evolved by rigging an outrigger paddling canoe with a mast and sail. In the 1800s canoes used for a paddling race in the morning were rigged for sailing in the afternoon (Holmes, p. 212).

After western contact, canoe racing including sailing canoes declined, supplanted by western vessels ill suited for Hawaiian waters. There was a short-lived resurgence of traditional water sports beginning in 1875 when King Kalākaua decreed an annual regatta to celebrate his birthday on November 16, which included sailing canoe races among several other water sports. And in the 1930s there were several small regattas exclusively for sailing canoes, sponsored by wealthy patrons.

Teams gather at Keokea to set up canoes.

Teams gather at Keokea to set up canoes. Then in 1994 Mike Kincaid and Nappy Napolean decided to create a sail from Hawai‘i Island to Maui, tackling ‘Alenuihāhā channel. Mike’s crew included Manny Vincent, long-time president of the Kawaihae Canoe Club.

The start of the HSCA interisland racing series, which began in 1997, was originally on Maui, with Hawai‘i Island added in soon after. The summer-long series of races will take place at four to six week intervals and go from Hawai‘i Island to Maui, to Moloka‘i, to O‘ahu, and culminate at Waimea, Kaua‘i in August. “We think of it as stitching together the whole chain of the eight main Hawaiian Islands,” said Kalaʽi.

Team Hulakai and Captain Jun Balanga set out from Keokea

Team Hulakai and Captain Jun Balanga set out from Keokea Jun Balanga, canoe paddling and sailing coach, Ka Piko Kai sailing canoe captain and owner of Hulakai Surf and Paddle at Mauna Lani, has sailed the HSCA series for the last six years. “I grew up in Lanikai, on the water. What started me in canoe sailing was sailing, period. Before windsurfing, I sailed Hobie Cats. We grew up paddling. Paddled with Lanikai from 12 years old. Then I got into canoe sailing,” said Jun.

His first sail was with Kala‘i Miller. “I really got hooked. We went from Kā‘anapali. We passed whales and they never even knew we were coming. We flew right by these guys. We had one breach and land right on our track behind us,” said Jun.

The Kēōkea to Hāna race was his first. “You’re leaving Kēōkea and all we have in front of us is clouds. You watch the angle the water comes in on, follow your wind chop, the angle of your sail. You’re running that line and you got everybody in the boat believing in you. Never matter when we get there but let’s do this together. The wa’a brings people together,” said Jun.

When he’s not racing interisland, he’s coaching. “What we do here is I set up and sail a lot of four-man. That’s the beginning. We get the feeling of the shoreline. Then I’ll take them to rougher water and wicked winds. The year before I took six young women, all moms, on the Kēōkea race. I wanted them to experience what I felt and how it can change your life,” said Jun.

Assembling and lashing canoe.

Assembling and lashing canoe. On the shore at Kēōkea, crews will rig the canoes. “It’s all in pieces. You rig the canoe together like you would a traditional six man. You put the ama (outrigger float) and the ‘iako (outrigger boom) together, put the covers on and step the mast,” said Olukai canoe captain Marvin Otsuji.

The set of the sail will be determined by wind, swell direction and intensity. Setting the sail takes knowledge of the conditions and the ability to see what lies ahead. “The way you set the sail on shore, it’s got to run that way all the way to the end. You can do one slight adjustment maybe, but you’re stuck with what you decided, it’s your future,” said Jun.

The sailing canoes do well with a broad reach and for the Kēōkea to Hāna race, the idea is to gauge the course to approach at a point east rather than west of Hāna. “If you come in too early, the whole crew going to be paddling for miles. Really rough. The boat is all over the place, the sail is just flapping,” said Jun.

Olukai, Marvin Otsuji captain, rides the channel.

Olukai, Marvin Otsuji captain, rides the channel. Canoe sailing is all about the balance between, “the resistance of my steering and the effort of my sail,” said Jun. Which means that how the sail is set and how the canoe is pointed are key to making the most of the wind and waves. “When it gets super windy, the teams that do well are the ones that learn how to spill the wind, not capture it. You have to learn how to monitor it. Being able to find the sail trim that allows you to go forward and spill it efficiently so you’re not wearing the steersman out,” said Marvin.

Each leg presents different conditions that need to be adjusted for. For the Kēōkea to Hāna run, “We stand the sail up a little more and move it towards the center line of the boat. What that does is create a pocket in the sail to store wind,” said Marvin.

Canoe sailing combines paddling, surfing and sailing into one, demanding a complex set of skills with the most successful teams made up of crew that are both paddlers and sailors. The winning canoe is the one that can take advantage of wind, swell and paddle power.

“Our main goal is to catch waves. You still have to have the paddle part to get you into the waves and there’s points where the wind dies and the angle changes a bit. You have to have really solid paddlers. But you need both a sailing crew and a paddling crew and you have to learn how to manage that,” said Marvin.

“Captains need to know how to move the crew to respond to the demands changing conditions. If two guys steering, we on fire. No eating, no drinking. You better have hydrated last night. Two would be paddling, two in the tramp, two steering and one will run the bailing. Number four still got to help run some backstays. You have to be synchronized and move together,” said Jun.

When the canoes depart from Kēōkea, Hawai‘i Island photographer Gloria Reed will be offshore in an escort boat. Gloria started as the HSCA’s photographer twenty years ago while working as a full time nurse. “I was shooting for Pacific Paddler, and a friend of mine, Thomas Kemper, was building a three man and wanted me to take some professional shots,” said Gloria.

When Gloria was invited to come along on an interisland race she was hooked. “It isn’t about money or prestige. It’s my passion. I feel honored to be part of a really special ‘ohana,” said Gloria.

Photographing canoe races is like riding a roller coaster. “There’s big swells, really rough and I have to brace myself in and pay attention to what I’m doing. There are moments out there that I’ve been scared,” said Gloria.

Or like doing survivalist training. “You’re cold and you’re so tired and still waiting for the last canoe to come in. Every canoe gets a photo, whether they come in first, second or last,” said Gloria.

Wind, swell, current in the Hawaiian channels creates the constant potential for a canoe to huli (flip). Then Gloria’s job changes as swiftly as the winds. “I put my camera away and I’ve literally jumped into the water to help,” said Gloria.

And at times it means missing out on a shoot entirely. “At the Nā Holo Kai race last year, Olukai flipped right off Ka‘ena Point,” said Gloria. “I had to go back to Hale‘iwa with the crew and the canoe. It was really sad for me because Nā Holo Kai goes to my home island,” said Gloria.

Although the equipment for today’s sailing canoes is updated with modern materials, the dance with the ever-changing ocean and winds are the same. “When you approach the shore, what you see, your mind goes out to how it used to be when the Polynesians approached a new place. I want to give everyone the opportunity and one chance to do something that brings the past back. That’s an honor and it’s huge,” said Jun.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed