Aerial view of Kohanaiki. Photo courtesy of Kohanaiki Shores LLC

Aerial view of Kohanaiki. Photo courtesy of Kohanaiki Shores LLC He heads down the lava strewn trail lit by the first rays to peak over Hualalai. Almost to the shore, he stops at a pond to collect opae ula, small shrimp that he will use for bait. Continuing on he recognizes Makua, who is already setting his traps. Kalani stops to observe the north and south currents facing off, a restlessly undecided ocean and moves south to set his traps.

Historically, Kohanaiki makai was a gathering place for shoreline fishing, salt collection and gathering opae ula from anchialine ponds by ahupuaʽa residents. Reggie Lee, park cultural advisor, lineal descendent and son of recently passed master weaver, Elizabeth Lee remembers, “My mom's story is they used to come down here and fish. We were shoreline fisherman. They used to dry and salt the fish. They'd go up on a donkey. My grandfather used to trade all the way up to Kalaoa. We even dyed our own net using the bark of the kukui tree. We wanted it dark brown or red to camouflage it.”

Then one day Karen and husband Gary Eoff met Angel Pilago. “We met Angel and his wife Nita at the beach. Angel knew about the work of the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation (NHLC) and he was a visionary and a strategist. As president of the Kohanaiki ʽOhana, he and his wife Nita navigated us through the legal battles,” said Karen.

Based on two Supreme Court decisions, the impact of any development on the gathering and usage rights of Native Hawaiians, as well as the environment must be taken into consideration. Following these decisions in 2000, Hawaiʽi State adopted Act 50, which required a cultural impact statement as well as an environmental one.

Professional legal support in combination with an activated community eventually won the day. Rebecca Villegas who was born and raised in Kona and grew up at Kohanaiki was one of many voices raised. “When I was 14 years old I gave a speech to the panel requesting that efforts be made to protect Kohanaiki. Growing up at Kohanaiki, it has been a place where I've celebrated my own birthdays and my family’s birthdays. I raised my daughter there. It's a grounding place, not only for myself but for the whole community,” said Rebecca.

The legal battle over, in 2001 Harry Kim brought all the stake holders to the table and after two years of meetings, a good faith agreement was forged. The zoning changed from resort to open space along the shoreline, with the developer donating 100 acres to the County of Hawaiʽi for the creation of Kohanaiki Beach Park.

Since that time the corporate entity, now Kohanaiki Shores, has honored the agreement, creating a public park along the shoreline with camping, bathrooms and showers. They have also complied with the highest standards of environmental protection, creating an Audubon award winning sanctuary for such endangered birds as the Hawaiian stilt and the sooty tern.

Lineal descendant Reggie Lee harvesting ipu gourds in the canoe garden. Photo by Jan Wizinowich

Lineal descendant Reggie Lee harvesting ipu gourds in the canoe garden. Photo by Jan Wizinowich Although many changes have taken place since Kohanaiki mauka residents traveled to the shore for sustenance, today Kohanaiki is carrying on in the spirit of community resource, the perpetuation of Hawaiian cultural practices and sustainability.

Turn off the traffic-choked highway and one is immediately plunged into an eye-of-storm calmness. A narrow road lined with great heaves of lava, winds towards the sea. The road narrows and curves left running parallel to the shoreline and a series of campsites tucked under the numerous tree heliotrope. A little further on a large collection of young surfers ride the southern summer swells while parents are watchful on the shore.

Colorful hand-painted signs with reminders to take care of the beach, drive slowly and live with aloha, line the entry drive, complements of Keiki Surf for the Earth, a contest for youth 14 and under, now in its 22nd year.

It’s not just about surfing though. “Kids have access to a space that is safe and healthy where they can learn and grow and have an understanding of their kuleana. They clean up marine debris, take care of the reef ecosystem and learn how to conserve water and reduce one use plastics,” said Rebecca.

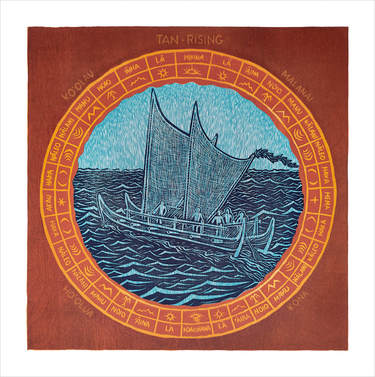

The road ends and a foot path continues past the halau, Ka Hale Waʽa, today having its thatching repaired. An ahu and lele stands south of the halau and forms the entrance to a 17’ diameter star compass, designed by Gary and Kalepa Baybayan and used to teach way finding.

Drawn to the star compass’s connection to canoe culture, Kumu Keala Ching brings kūpuna to the park. “I brought kūpuna down to learn about the dial itself, the movement, the celestial stars summer solstice and winter solstice and to bring information to our people by learning about the area,” said Kumu.

Beyond the star compass is the canoe garden backed by some of the 200 anchialine ponds that dot the area. Carved out of a space once choked with fountain grass and naupaka the canoe garden contains large patches of ipu gourds, sweet potatoes and kalo.

Besides providing sustenance and materials for the creation of traditional implements, the garden is a living laboratory of sustainability that teaches learners by allowing them to plunge their hands into the soil and life’s mysteries hidden there.

Lanakila Learning Center students preparing 'ie'ie. Photo courtesy of Karen Eoff

Lanakila Learning Center students preparing 'ie'ie. Photo courtesy of Karen Eoff Kohanaiki Beach Park provides an ideal setting for students to engage in authentic cultural and environmental learning. Neighboring Innovations Public Charter School has a bi-annual hands-on science program at the park. “We incorporate a lot of ethno-mathematics into our curriculum. Cordage and cordage making are one of the corner stones of our science curriculum,” said Meg Dehning, Innovations middle school teacher.

The students experience a combination of hands-on engagement to learn about environmental science, cultural practices and give back with service work. “They had an opportunity to learn about the culture / ecological heritage of that particular section of the coastline. The students got to do lauhala weaving with Aunty Elizabeth Lee, learn to strip hau and took part in the ceremony for the star compass that was presided over by Kalepa Baybayan,” said Meg.

Service learning allows students the chance to give back at the same time they were receiving. “They really liked the hands on work, especially when it came to learning to weave from Aunty Elizabeth or clearing the pond or helping dig the garden. It gave them the opportunity to learn in an authentic way. These are things that you just can't teach in the classroom,” said Meg.

“Realizing how much work went into gathering the leaves, cleaning and stripping and the whole thing. They understand the hard work that goes into it and they really appreciate the manaʽo that's passed down by cultural practitioners because they've been on the receiving end of it. A whole different level of appreciation,” said Wendy.

Next year’s program will focus on fiber art and cordage. “We hope to help them with their cordage garden. Gary’s going to teach the kids how to make cordage out of hau and coconut husk and hopefully the kids can help weave the hau to make the entry rope for the front of the halau and to learn to lash the double-hulled canoe that they're in the process of building. They have to come up with two miles of cordage,” said Wendy.

The Kohanaiki Beach Park provides a sense of place and connectedness to the past and the future. And it’s an example of what can be done when people bring their best intentions to the table. “The park is a model for a better community where the shore remains with for and by the community, and managed by a consortium of county, community and developer representatives. The vision is that the model be perpetuated elsewhere. The coastline must be available for everyone,” said Rebecca.

For more information contact:

Camping permits: https://hawaiicounty.ehawaii.gov/camping/all,details,57824.html

Contact writer: [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed