Aunty Deedee Keakealani Bertelmann: “For us, harmony is a big deal. We can’t sing and not have harmony, yeah? So with music, harmony is important, but when you look at life, harmony is also really important. We have to get along with each other. That’s what we based our life and our children’s lives on.” These are the layers and traditions of Hawaiian music that have traveled through the generations and call out from the Bertelmann garage on a regular basis.

Aunty Deedee: “That’s a question you don’t often think about, yeah, were did it all start? You don’t even think about it cause you just do it. So when somebody poses that question: ‘Who taught you?’, I just remember as children in our home there was music all the time. It just kind of grows on you. Some people say that it’s in your genes and perhaps it is. I just know that in our home my mom sang. My mom had a beautiful soprano voice. My dad sang. My dad also played instruments; he played the ukulele and the banjo. There was always a comment that, Uncle Kimo, his name was Kimo, he would start a song but he never finished the song."

Learning an instrument the Hawaiian way is done by: Nana ka maka (look with your eyes); hoʽolohe pepeʽiao (listen with your ears); paʽa kou waha (close your mouth); hana ka lima (work with your hands).

Aunty Deedee: “How did I even learn to play the ukulele? I just remember having it in my hand. I can’t remember where it started. It must be cause my dad. If an ukulele is laying around, today it’s no different. If they see you playing they eventually pick it up. So one of my granddaughters, her name is Anuhea, she’s 16, she’s playing the guitar now and she’s fortunate that she has her Uncle Chadd but she also learns a lot on her own so I’m watching the process and she’s teaching herself. And then when Uncle Chadd’s here she’ll say, ‘Uncle, what about this and how do you do this?’ So I think it’s both. You learn a lot on your own and you learn a lot from others. She’s picking up a lot from the computer. Going on the computer and just learning from that.”

Pomai: “To us, we actually had really good teachers. It was the garage and actually the kitchen in this house is pretty famous too. If the walls could talk….Part of why I learned how to play was that I used to watch Aunty Auhea Puhi who used to sit on the freezer with us and we used to sit on the counter in the kitchen when it got too cold. We were all packed in there and I remember I used to be amazed that she used to change chords so fast. I was thinking we have a bunch of ukulele’s on the wall but I don’t know how to play em yet.

"It was the same for Aunty Lorna’s garage. Because we used to go to Aunty Lorna’s house all the time, especially when Uncle Sol and Uncle Richard would come. The falsetto when the Hopiʽi brothers would sing. Amazing. Sometimes we’d be outside playing on the road or the backyard and we’d hear these haʽi that these men were singing and you’d come flying through to the front and you just kind of stand there like what is going on? The community was really good to us.”

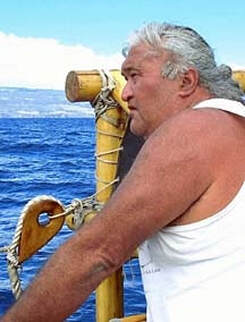

Clayton Bertelmann

Clayton Bertelmann Kuʽulei: Mentioning Uncle, Uncle Clayton Bertelmann is the father, husband, Uncle. But this hale, this kitchen, this house, was home to many kanikapila. Most of the time for no occasion. Sometimes for occasion. But this is a childhood memory. This house and music, Uncle Clayton. There’s one particular song, “Pua Hone”. For me, I hear that song and I see this house or the kitchen or Uncle.

The ʽāina has inspired many Hawaiian mele; legend associated with particular places is connected to contemporary stories, linking place with the past and the future. Kealiʽi: “This mele I’m going to sing for you right now is a mele titled Nā Puʽu. If you look, the puʽu to my left is puʽu hokuʽula and the puʽu to my right is pu’u hoaʽhoaka and it’s a mele that compares those two pu’u to a pair of lovers. Two friends of mine who are in a love affair; I wrote it to honor those two friends of mine. On the western facing slope there are two ohia trees and you can only see one from here. When I wrote the mele I was down in Lalamilo where you can actually see the trees and as I was sitting there composing the mele, those two ohia trees reminded me of the story of the lovers ohia and lehua. So in this mele it’s kind of intertwined this love story of ohia and lehua. But puʽu hokuʽula is the place also where the god and goddess Wao and Makuakuamana were wed. That landscape in particular for me represents the aloha between two people.”

Kuʽulei: “I have something to interject. If you do not know, now you will. Brother Kealii is the 2011 Kindy Sproat falsetto contest winner. And this is the song he won it with.” As Kealiʽi sings, we look out across the plains of Mauna Kea stretching behind him and feel Keali`i’s strong connection to the puʽu behind us, we can imagine for a moment that we have been invited into the great stories of this land.

Keali'i: "It was an honor to enter the falsetto contest this year. I entered for many reasons. There was a few times that I got to go and sit on the lanai at Makanikahio and sit with Uncle Kindy before he passed away. And it was an honor because our families were pili together. My grandfather and their ʽohana, there was such a closeness there. This mele I’m going to sing is a song that Uncle sang and if I’m not mistakes it was a song he learned when he was younger from the people in Miloliʽi. And really it’s a very simple song and it’s a song that just kind of talks about the delicacies from the ocean that we kanaka love to eat. I call it the fish song because I don’t think there was really a formal title for it. It was just a mele that he sang that talks about different types of fish and what you eat of that fish.”

Ke Ala a ka Jeep

Inā ‘oe e kau ana i ke ka‘a Jeep

He loa ke ala e hele ai, he kāhulihuli

Ma nā pi‘ina nā ihona piha pōhaku

‘Alo ana i nā pānini me nā ‘ēkoa

Ho‘opū‘iwa i nā pīpī a holo i kahi ‘ē

Pēlā mākou i hiki ai i kai o Waikapuna

A mai laila a Pā‘ula me kona hiehie

‘Ike aku i ke ana ‘o Puhi‘ula

Ho‘i hou aku i Nā‘ālehu me ka ka‘a Jeep

Hau‘oli ka helena me nā makamaka

Alu aku i Kalae a me Kaulana

A ‘ike iā Palahemo wai kamaha‘o

A hiki mai i ka hale o ka makamaka

Luana i ka la‘i ‘olu o Wai‘ōhinu

Ha‘ina ka puana me ke aloha

No ka ‘āina ka ua o Hā‘ao

The ranching life style is inextricably linked to Hawaiian music.

Pomai: “… beyond the fact that Kuʽulei and us are family and we’re related through culture, but [we are connected] more specifically through our ranching lifestyle. That lifestyle actually afforded us the opportunity to be with a lot of families. And all those families sang. Whenever rodeo was pau, we sang, whenever rodeo was happening and we didn’t have to be roping or racing or something like that, we were under the trailers, parked side by side with the canvas over and we were cooking and singing. We were really blessed to be raised in a good community where we always got together, equally important to what we got from home. That’s really what helped us too, to learn as much as we have. There’s that reinforcement too, not just within the household but within the community too.”

Kuʽulei: “…growing up and being around the cowboys. Their fun songs; songs that have been way into the night, early in the morning. And if you want, just to call them kolohe songs, or songs that have a rascal nature to them. When you have a chance to hear these songs, sometimes they make sense, sometimes not at all. But, you know these are the times you might find my father dancing on the table. When you hear him go ‘Batman’, that’s one of those songs.”

Keali`i: “We were raised singing and to love Hawaiian music. My father loved Hawaiian music. The Sons of Hawai`i records, we grew up listening to that. We had our own ranch; we were raised on the ranch. My dad them entered rodeo and they did those sorts of things. The music comes with the lifestyle and because they were cowboys, we loved country music and we still do. I’m hoping that my sister will sing a song.”

Pomai: “We grew up watching Roy Anthony. I don’t know if anyone remembers Roy Anthony, but he was a big time live deal for us over here as little kids. And we were really stoked because he’d always end up over here at our parties, through some way shape or form.”

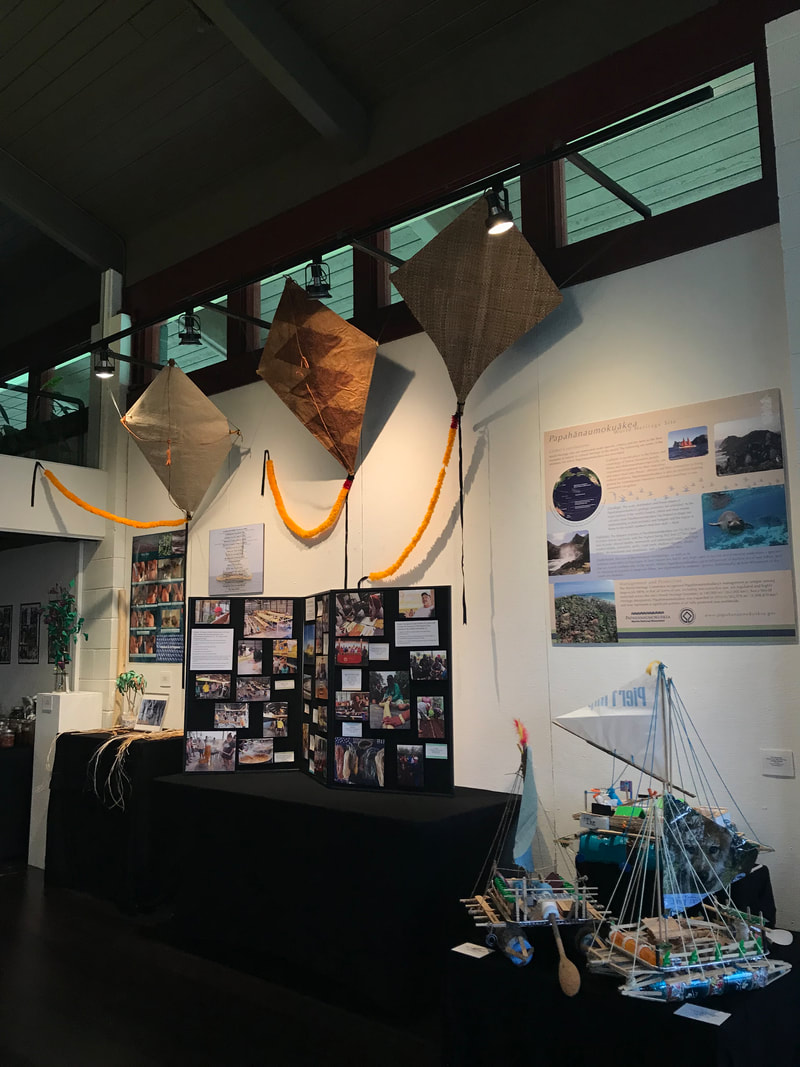

Makali'i under sail.

Makali'i under sail. The Bertelmann ʽOhana are musicians, dancers, composers and ranchers, but they are also of the sea. Uncle Clay was instrumental in the creation of Makaliʽi, Moku o Keawe’s voyaging canoe as well as the onboard educational program that now takes place annually. Pua Case: “I never knew this yard for music. I knew this yard and that kitchen table to be a place of very serious work and still is. Every time I come here, we in serious planning. You know we doing something serious. And that’s how I know this yard. From the moment I sat on that table and Clayton Bertelmann was planning to build a canoe for his brother (Shorty), I’ve know this house to be that. So they have a whole other side of them that hopefully we’ll bring out. They’re not just ranchers and not just singers, but they are also people of the sea.”

It was through the canoe that Pomai met her husband Chadd Paishon, who had sailed on the Hōkūle’a with Uncle Clay as his captain.

Pomai: “Chadd’s family is a really amazing family. His mom is an Aki and his dad was a Paishon. His grandmother was a beautiful, beautiful song writer. Many songs of which you hear today being sung on the radio. He has roughly, currently alive first cousins, about 40 of them. Forty-seven of them. And they all sing.”

Chadd: “It’s no different like mom was saying for us for my family. My weekends were spent with my grandmother. Like Pomai said, she was a hula dancer, singer, composer. But for us growing up in our house on Oʽahu, all of us cousins all knew what we were doing on the weekend. We were going to be with grandma at somebody’s house. You were either going to be learning a song that she wrote or you were going to be learning the hula to that song. That’s the only two choices. Either you sing or you dance, you pick. It’s going to be one of the two. So I picked singing, but I also dance. Whenever we do have the chance to get together we all sing.

They are classmates with my middle daughter and I will say, Nahe will come home and say, ‘The sisters taught me F today.’ So Aunty, yet another example of how, it’s to hoʽomau and that Ipo and Kaʽala are teaching my little one.”

Keali`i: "This mele they’re going to sing: For a couple years, the three kids, my sister in-law worked for the University in Hilo. They would stay in Hilo and the kids would go to school in Keaukaha and this mele they’re going to sing is a mele about Keaukaha, a song titled Kamalani o Keaukaha."

Kamalani o Keaukaha by Lena Machado

Nani pua `a`ala onaona i ka ihu

E moani nei i ka pai pu hala

Mehana ku`u poli i ka hanu a ka ipo

I hui puia me ke aloha pumehana

Beautiful, flowers sweetly fragrant

Scented, gentle breeze in groves of hala

My heart is warmed by my darling's breath

Kiss sweetly fragrant with the warmest love

Carnation i wili `ia me maile lauli`i

`Iliwai like ke aloha pili polu

Darling sweet lei onaona o ia kaha

E ho`oipo nei me ke Kamalani o Keaukaha

Carnation entwined with the small-leaved maile

Love moistly clinging, level as water's surface

Darling, sweet fragrant lei of this place

Sharing love with Keaukaha's favored child

Pomai: “There’s songs that are really, really beautiful to listen to and they all have their own messages. Each song, whether it’s traditional or not has a story. Every one of them, if you listen carefully enough, if you pay attention to it enough, if you’re actually able to sit quietly and listen to it and become ma`a (familiar) to it, you recognize there’s a story in it. And so I think we’ve been very, very fortunate to grow up in an amazing place, but we’ve also been very fortunate to grow up with amazing people. Who shared music with us. In many, many ways I don’t think they realized they were teaching us something that was invaluable. To understand and to become familiar with our language again and then to interpret and be able to understand all of the content and all of the lessons that are embedded in those stories so our lives have been more rich because of that. That is something we value.”

Kuʽulei: “Last week at Aunty Lorna’s there were many highlights, but one of my highlights was hearing Uncle Willy say to his children, who were there and his two grandsons that were there that he was happy that they were hard workers. In essence to me he was conveying the message that he was proud of them. Then to hear Willy Boy say mahalo to his mother and his father for everything.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed